US Coal Plants Face New Rule: Capture CO2 or Shutter

By Julia Attwood, Industrial Decarbonization Specialist, BloombergNEF

Published 06-04-24

Submitted by Bloomberg

Originally published on about.bnef.com

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s final rule on carbon pollution from power plants may not be the boon for carbon capture that it seems. While existing coal plants will have to install the technology in order to keep running, all gas peakers are exempt, and rules for existing gas plants are on hold. This should push the US power system towards cheap renewables and gas peakers, and force coal plants to retire.

- With its final rules on carbon pollution standards for power plants, the EPA gave with one hand and took away with the other. To address the threat of litigation from gas power producers, the agency put its requirements for existing US gas plants to reduce their emissions on hold, for now. The organization plans to revisit the requirements, but for the moment they will only have to comply with best practice emissions limits based on efficiency. Gas peaker plants were also exempt, but new baseload plants will still have to install carbon capture systems by 2032. In a nod to environmental groups, the EPA also brought forward the required date of retirement for unabated coal plants by a year, to 2039.

- The rules stipulate that emissions must be abated by 90% for existing US coal and new baseload gas plants through carbon capture and storage (CCS). Hydrogen firing is no longer allowed as an emissions abatement pathway. This is a tall order for CCS, which has so far only been used to capture a small fraction of the emissions from power plants.

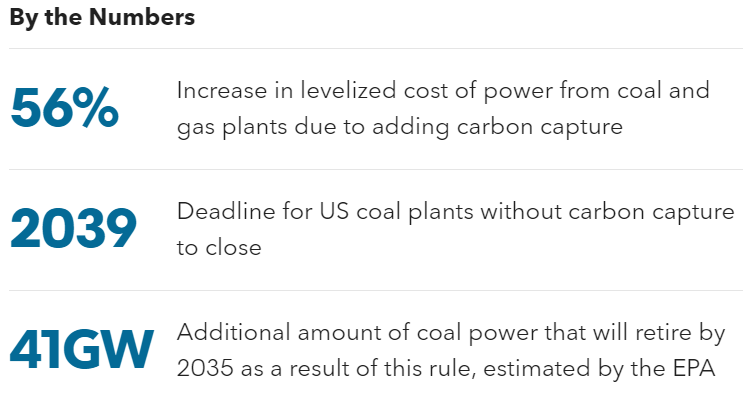

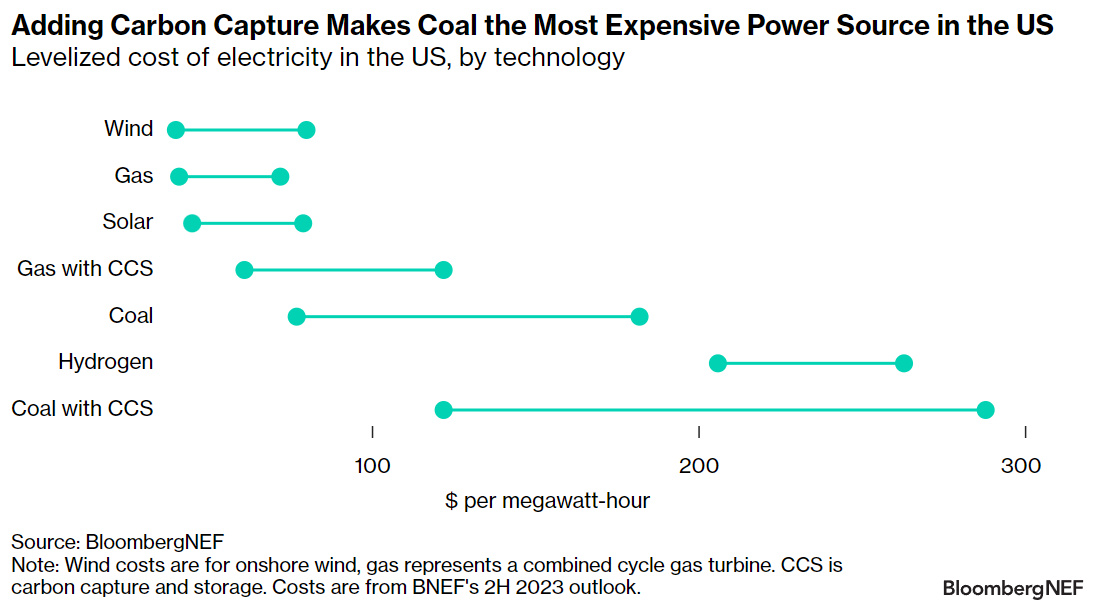

- BNEF estimates the levelized cost of electricity for new-build coal and gas coupled with CCS is $122-$288 per megawatt hour (MWh) for coal (including storage) and $61-$122 per MWh for combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT). Assuming mid-range values, CCS would increase power costs by about 56% for both forms of generation.

- While the exemptions may mean that less CCS than expected is actually built, there could still be important knock-on effects. Sequestering CO2 from even a fraction of power plants will require significant amounts of new transport pipelines and storage sites. These are large infrastructure projects that are typically built to serve multiple sites. Industrial emitters such as ethanol plants, integrated steel mills, cement plants and petrochemicals producers could all piggyback on infrastructure built to serve the power sector. This would remove a significant barrier to decarbonization for these sectors.

- Power plant operators plan to retire 44 gigawatts (GW), or 23%, of the 2023 operational coal fleet by December 2030, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). By 2032, when regulations on CCS come into force, only 143GW is expected to be operating in the US. The EPA estimates that an additional 30-40GW of coal power will likely be forced into early retirement due to this rule, unable to make a return on what would be an $800 million capital investment for the capture unit. This is equivalent to an annual emissions reduction of about 150 million metric tons of CO2 and would reduce the US coal fleet to around 100GW of capacity by 2035.

- Rapid load growth and calls for reliability could come to the rescue of the coal fleet. As concerns of rising data center power demand and industrial load growth sweep the country, an increasing number of system operators are raising concerns that dispatchable generation sources – coal and gas – are retiring faster than replacement capacity can come online. While gas plant economics are faring far better than coal, it does not offset reliability concerns. Large planned retirements in the gas fleet will offset announced gas capacity additions, resulting in a slight drop in operational capacity by 2030. The lack of final rules for existing gas plants and exemptions for gas peakers are likely to soothe some concerns over system reliability.

- Strong political opposition to federal environmental mandates (and perceived risks to fossil fuel plants) will rapidly attract lawsuits. Until the Supreme Court inevitably rules on the legality of the power plant regulations – and the November presidential election is decided – their durability will remain in question.

- Of more concern is the ticking clock on issuing regulations for existing gas plants. If the EPA does not issue a final rule for existing gas plants before the inauguration (January 20, 2025), then a new president can more easily and quickly revise it, and a Republican-majority Congress could repeal it through the Congressional Review Act.

BNEF clients can access the full report here.

About BloombergNEF

BloombergNEF (BNEF) is a strategic research provider covering global commodity markets and the disruptive technologies driving the transition to a low-carbon economy. Our expert coverage assesses pathways for the power, transport, industry, buildings and agriculture sectors to adapt to the energy transition. We help commodity trading, corporate strategy, finance and policy professionals navigate change and generate opportunities.

Bloomberg

Bloomberg

Bloomberg delivers business and markets news, data, analysis, and video to the world, featuring stories from Businessweek and Bloomberg News.

More from Bloomberg