The Potential of Internal Carbon Pricing Policies

Which organizations are ready to lead the way and use fine grain, transparent emissions data to drive emissions reductions before regulations make it mandatory?

Published 10-19-16

Submitted by Scope 5

Recently, an increasing number of organizations have started putting a price on carbon. This is the first step in internalizing the price of carbon emissions, which will certainly help efforts to lower global emissions. But to fully realize the potential of carbon pricing, it’s necessary to go beyond simply putting a price on carbon – the cost of carbon will have to be felt directly by those emitting it.

Microsoft’s Internal Carbon Fee (ICF) is probably the most sophisticated carbon pricing policy today. Disney has adopted a similar model. The potential of these programs hinges in large part on the underlying emissions inventory which is a crucial piece of the ICF. In this post, I’d like to take a deeper look at the model pioneered by Microsoft and then propose ways in which the model might be further improved.

Start by Setting the Carbon Price

The first step in implementing an ICF is setting a carbon price. To do so, the organization designs an investment strategy to reduce carbon(1). The organization then conducts an emissions inventory and divides the annual cost of its investment strategy by its total annual emissions to arrive at its carbon price:

$15,000,000/1,000,000 tonnes = $15/tonne CO2e

Impose Internal Fees

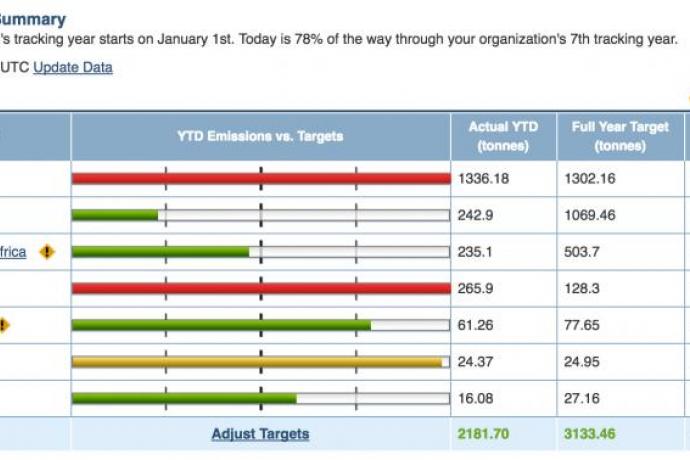

The internal fee is the exciting part. The total cost of the investment strategy is the fee. This fee is distributed across groups within the organization in proportion to each group’s contribution to the organization’s total emissions. As a result, the groups are motivated to understand their emissions and to reduce them.

The Emissions Inventory

Implementation of an ICF requires the collection of data related to emissions generating activities. In Microsoft’s case the relevant activities are energy and air travel (different activities may be material to different organizations). The activity data is converted to emissions data, resulting in the emissions inventory. The emissions inventory serves two needs:

It provides a number for the organization’s total emissions. This number is used to set the carbon price as described above.

It calculates the emissions for which each group is responsible and thereby allocates the appropriate portion of the overall fee to each group.

The calculation of an organization’s total emissions is an important step, because it is used to determine the internal carbon price, but it can happen ‘behind the scenes’ and relatively infrequently (such as annually). In fact, many organizations already produce an annual inventory that they report to organizations such as the Carbon Disclosure Project or that they use for their annual sustainability report.

What Makes a Great Emissions Inventory

Organization wide, annual emissions inventories may be the norm today. However, many of the executives that we work with at Scope 5 are looking at their group’s emissions on a more frequent basis because that level of detail better enables them to drive decisions that make a difference.

As ICFs proliferate, such decisions will have real cost consequences to these executives and as such, stand to result in real emissions reductions. For these outcomes to truly be realized, emissions inventories must be:

Transparent – widely visible and easily understood

Granular – both temporal and spatial, the finer the better

Accuracy – consistent, accurate and precise accounting methodology

These characteristics enable individuals to correlate their group’s specific operational activity with fluctuations in emissions levels. They foster a sense of accountability and responsibility across the organization. They spur innovation to improve efficiencies.

Transparency

Transparency is best served when the relevant data is democratized. Data illuminating the organization’s activities and resulting carbon impacts that might otherwise be siloed should be made available to the organization’s stakeholders. When employees are able to easily see the impacts of their activities, how they compare to their peers and their part in the ‘whole’, they are motivated to take responsibility and to seek improvement.

Studies show that employees, in particular millenials, value this kind of transparency and tent to be more engaged, ultimately benefitting their organization. Anecdotally, we’ve seen this sort of transparency motivate green teams at several Scope 5 clients in recent years. The more these teams see, the more they want to improve their numbers.

Granularity

Granularity can be temporal or spatial. Temporal granularity refers to the frequency at which the organization conducts their emissions inventories. Spatial granularity refers to the size of the units to which emissions are attributed (ranging from business units to departments to individuals to specific activities).

Temporal Granularity

While many organizations engage in a sort of backward looking annual inventory, they may be missing the value of a dynamic, forward-looking inventory that is continually up-to-date. By looking at say, monthly data, it is possible to make operational decisions and adjustments that avert emissions before they have been emitted. The carbon fee motivates this kind of dynamic engagement because it can lead to operational improvements that reduce a group’s costs.

Spatial Granularity

The carbon fee minimizes the tragedy of the commons that so hampers progress in tackling sustainability issues. Most employees of a large manufacturing company for example, may harbor some notion of ‘I wish my organization wouldn’t generate that much pollution’, but in a big organization, they are unlikely to do much beyond that. When a fee is pushed down to individual groups, the consequences are more granular – individuals are more likely to see and feel their contribution and as a result, are more likely to take responsibility and to act.

One form of spatial granularity is in the reduction of the group size to which responsibility is assigned. Another form is in the allocation of the fee to different activities. When an employee sees that their group’s total carbon emissions are so many tonnes per year, they may feel a sense of responsibility but are likely ill equipped to do much about it. However, when one sees that their flight to London results in 1 tonne of CO2 emissions and that flying business class would double those emissions, they are empowered to make different choices, thereby reducing their group’s carbon fee and making the world a better place.

Accuracy and Precision

To date, most emissions inventories are voluntary(2). Such voluntary emissions inventories do not have to be very precise or accurate. However – as soon as fees are levied based on the result of an inventory, it is necessary for that inventory to be accurate and precise. Emissions factors must be agreed upon ahead of time. Emissions must be prorated to exact dates. Accounting methodologies must be clear and consistent.

The State of the Art

Microsoft and Disney represent the state of the art in ICFs. Some of these organizations’ employees are aware that their organization implements an ICF. Very few have fine grain visibility into their organization’s emissions inventory. Both Microsoft’s and Disney’s internal fees are pushed down to the business unit level(3) but no further. Microsoft’s emissions inventory is conducted quarterly. Disney’s is annual.

Conclusion

An internal carbon fee can serve organizations in a number of ways:

It can save costs

It can reduce environmental impact

It can demonstrate corporate social responsibility

It can drive innovation

It can promote employee engagement

To fully realize the potential, the ICF needs to be transparent, fine grain and accurate. With Microsoft and Disney as examples, U.S. businesses are off to a good start but still have a way to go. Scope 5’s work with our clients over the past 5 years confirms the potential of the ICF model. Which organizations are ready to lead the way and use fine grain, transparent emissions data to drive emissions reductions before regulations make it mandatory?

Yoram Bernet is the CEO of Scope 5. Scope 5 helps organizations collect, track, analyze and communicate sustainability data, ranging from greenhouse gas emissions reporting to identifying opportunities to reduce waste, water and other resources.

1 In Microsoft’s case this strategy includes purchasing green power, investing in efficiency innovations and buying offsets for emissions that cannot be eliminated.

2 Generally, only organizations emitting over 25,000 tonnes annually have been bound to report by the EPA.

3 Typically thousands of employees.